Hearts And Minds: How Stress And Negative Emotions Affect The Heart

The links between the heart and the mind are harder to measure than those between the heart and the waistline. But a growing body of evidence suggests that psychological factors are — literally — heartfelt, and can contribute to cardiac risk. Stress from all sorts of challenging situations and events plays a significant role in cardiovascular symptoms and outcome, particularly heart attack risk. The same is true for depression, anxiety, anger, and hostility, as well for social isolation. Acting alone, each of these factors heightens your chances of developing heart problems. But emotional issues are often intertwined: people who have one commonly have another. For example, psychological stress often leads to anxiety, depression can lead to social isolation, and so on. When combined, their influence is compounded.

In some cases, you can make changes to ease your burdens — by changing jobs or relationships, for example. But some of the stress in our lives is simply impossible to avoid, and a moderate amount of stress can act as a positive, motivating force. The question is this: does reducing stress, or changing how you respond to it, actually lower your cardiac risk and the likelihood of having a heart attack? The answer isn’t entirely clear, although some preliminary results suggest yes (see “Relaxation and your health”). The uncertainty reflects the challenge of doing research into psychological stress, which is so often accompanied by behaviors that are risky in their own right, such as smoking and overeating. It also reflects the challenge of persuading people to make changes in the way they think and behave.

The stress response

Your body reacts to life-threatening stress (“The house is on fire!”) with a “fight-or-flight” response. The brain triggers a cascade of chemicals and hormones that speed the heart rate, quicken breathing, increase blood pressure, and boost the amount of energy (sugar) supplied to muscles. All of these changes enable your body to respond to an impending threat. Unfortunately, the body does a poor job of discriminating between grave, imminent dangers and less momentous, ongoing sources of stress. When the fight-or-flight response is chronically in the “on” position, the body suffers. This chronic stress response can occur if your body is persistently exposed to stressors that overwhelm its adaptive ability. Think of it as your body in a constant state of “short-circuiting.”

The release of stress hormones also activates the blood’s clotting system. And long-term mental stress appears to stimulate the body’s production of LDL and triglycerides, to interfere with blood pressure regulation, and to activate molecules that fuel inflammation (see Figure 4).

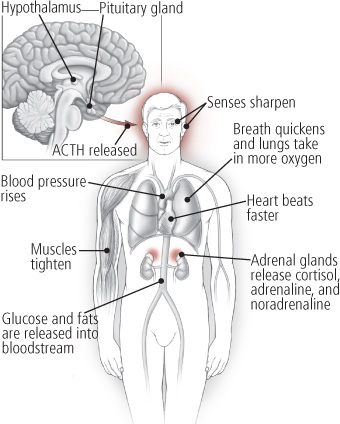

Figure 4: The stress response

The hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands make up the HPA axis, which plays a pivotal role in triggering the stress response. By releasing certain chemicals, such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol, the HPA axis rouses the body for action when it’s faced with a stressor. As the illustration reveals, the effect of this release of hormones is widespread. Senses become sharper, muscles tighten, the heart beats faster, blood pressure rises, and breathing quickens. All of this prepares you to fight or flee in the face of danger.

Stressors that harm the heart: What’s the evidence?

Everyone knows that particular events, such as the death of a spouse or being fired from a job, are extremely stressful. Yet research indicates that less dramatic but more constant types of stress may also harm your heart. In 2004, The Lancet published a study that involved over 24,000 participants from 52 countries. Roughly 11,000 patients who had just had a first heart attack were asked, as they left the hospital, about various forms of stress they had experienced in the preceding 12 months. The questions probed reactions to job and home stress, financial problems, and major life events. Members of a control group, who were matched to the patients for age and gender but had no history of heart disease, underwent similar assessments. Despite variations in the prevalence of stress across countries and racial or ethnic groups, increased stress levels conferred a greater risk for heart attack than did hypertension, abdominal obesity, diabetes, and several other risk factors.

Many other studies have also documented that various forms of stress can take a toll on the heart:

Workplace stress. Women whose work is highly stressful have a 40% increased risk of heart disease (including heart attacks and the need for coronary artery surgery) compared with their less-stressed colleagues. These findings come from the Women’s Health Study (WHS), which included more than 17,000 female health professionals. For the study, researchers defined job strain as a combination of demand (the amount, pace, and difficulty of the work) and control (the ability to make work-related decisions or be creative at work). Earlier studies found similar trends among men: one documented a twofold higher risk of newly diagnosed heart disease among men who felt the rewards they received at work weren’t compatible with their effort. Finally, working overtime hours seems to overtax the heart, as evidenced by a study that found a nearly 70% higher risk of heart disease among people who worked an average of 11 hours per weekday, compared with those who worked normal working hours (seven to eight hours per day). The study, which followed nearly 7,100 people (none of whom had heart disease at the outset) for just over 12 years, was published in Annals of Internal Medicine in 2011.

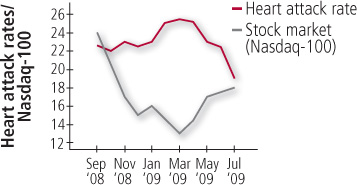

Financial stress. Heart attacks rose as the stock market crashed, according to a 2010 report in The American Journal of Cardiology. Researchers at Duke University reviewed medical records for 11,590 people who had undergone testing for heart disease during a three-year period, and then compared monthly heart attack rates with stock market levels. Heart attacks increased steadily during one eight-month period — September 2008 to March 2009 — that was particularly bad for the stock market (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Heart attacks rise as stocks crash

Heart attacks increased steadily during one eight-month period that was particularly bad for the stock market.

Caregiver stress. Women who cared for a disabled spouse for at least nine hours a week were significantly more at risk of having a heart attack or dying from heart disease compared with women who had no caregiving duties, according to findings from the Nurses’ Health Study. This large study followed more than 54,000 female nurses over a four-year period.

Disaster-related stress. Following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, researchers asked 2,700 American adults to complete an online survey of physical and mental health. People who had high levels of stress immediately after the attacks were nearly twice as likely to develop high blood pressure and more than three times as likely to develop heart problems during the following two years compared with those who had low stress levels.

Earthquakes also trigger stress-related heart problems — not just in their immediate wake but for years afterward, some research has shown. Sudden cardiac deaths rose sharply immediately after the 1994 earthquake in the Los Angeles area, and hospitalization for heart attacks jumped on the day of the 1995 temblor near Kobe, Japan. A longer-term follow-up of another major earthquake in Japan (Niigata-Chuetsu in 2004) revealed that death rates from heart attacks rose during the three years after the quake compared with rates during the five years prior to the disaster. The property damage, loss of livelihood, social disruption, and other stressful events resulting from the quakes probably explain this trend, say the study authors, who published their findings in the journal Heart in 2009.

Researchers are also beginning to study the effects of other stressors on heart health, including neighborhood-related stressors such as violence or growing up in a disadvantaged environment marked by adversity and discrimination.

Other mental health concerns

Given the widespread prevalence of both heart disease and mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, it’s not surprising that they often occur together. Understanding how they interact — and, more importantly, how they can be prevented, minimized, or treated — may help people feel better both emotionally and physically.

Depression. The relationship between depression and heart disease is a two-way street. Not only does depression appear to promote heart disease, but it can also result from a heart attack. Studies suggest that people who are depressed are about twice as likely to develop coronary artery disease, and that people who already have heart disease are three times as likely to be depressed as other people. For as many as one in five people, depression follows a heart attack. Finally, depression is an independent risk factor for a subsequent heart attack in people who’ve already had one. This may be in part because people who are depressed are less likely to take proper care of themselves — they might continue to smoke, fail to take their medications regularly, or not exercise enough.

Whether you’ve had a heart attack or not, if you feel depressed, tell your doctor. Depression can be treated successfully with antidepressants, psychotherapy, or both. Treating depression can make you feel better and decrease your heart attack risk.

Anxiety. Between 24% and 31% of people with heart disease have symptoms of anxiety, according to various studies. But these findings are somewhat questionable, as some of the research relied on participants’ recollections or single objective “snapshot” assessments rather than using structured interviews to diagnose anxiety. Many studies have also lacked controls for factors such as lifestyle that could affect heart disease risk.

However, two studies that followed large numbers of participants over time addressed some of those weaknesses, such as controlling for confounding factors such as major depression (which often occurs in conjunction with anxiety). The results showed that generalized anxiety disorder — characterized by constant and pervasive anxiety, even about mundane matters — appears to increase the risk of heart attacks.

It’s also worth noting that severe anxiety — which may manifest as a panic attack — can mimic a heart attack (see Table 5). One analysis of studies involving people admitted to emergency rooms for chest pain found that 22% of those who underwent cardiovascular testing had panic disorder rather than heart disease. Another extremely common symptom related to anxiety, particularly in women, are palpitations — the sensation that your heart is racing or beating too fast.

As with depression, medications and therapy can help treat anxiety. Because anxiety often stems from stress, techniques that aim to quell the stress response can also be effective for easing anxiety.

Table 5: A panic attack or a heart attack?

Both a panic (anxiety) attack and a heart attack can cause shortness of breath, sweating, or dizziness. Below are some of the factors that help to differentiate a panic attack from a heart attack. (Note that anyone having these symptoms should seek immediate medical help.)

More likely a panic attack

- Sudden onset of fear or terror in conjunction with heart palpitations or chest pain

- Pain and discomfort tend to occur in the center of the chest

- Chest pain and other symptoms subside after 5 to 30 minutes

More likely a heart attack

- Gradual onset (over several minutes) of pain, pressure, or tightness in chest and upper body

- Pain may occur in center of chest but may also radiate to upper body (arms, shoulders, or jaw)

- Symptoms last at least 15 minutes without subsiding in intensity and may continue for hours

Stress-easing strategies

It’s nearly impossible to avoid all sources of stress in your life. While you can’t change the world around you, you can try to change your reactions and to manage your stress. Try the following to minimize your stress level:

Get enough sleep. Lack of sound sleep can affect your mood, mental alertness, energy level, and physical health.

Exercise. Physical activity alleviates stress and reduces your risk of becoming depressed.

Learn relaxation techniques. Meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, deep breathing exercises, and yoga are mainstays of stress relief. Your local hospital or community center may offer meditation or yoga classes, or you can learn about these techniques from books or videos. To get started, try a quick relaxation exercise (see “Quick stress-relief exercises”).

Quick stress-relief exercises

When you’ve got one minute. Place your hand just beneath your navel so you can feel the gentle rise and fall of your belly as you breathe. Breathe in. Pause for a count of three. Breathe out. Pause for a count of three. Continue to breathe deeply for one minute, pausing for a count of three after each inhalation and exhalation.

When you’ve got three minutes. While sitting down, take a break from whatever you’re doing and check your body for tension. Relax your facial muscles and allow your jaw to fall open slightly. Let your shoulders drop. Let your arms fall to your sides. Allow your hands to loosen so that there are spaces between your fingers. Uncross your legs or ankles. Feel your thighs sink into your chair, letting your legs fall comfortably apart. Feel your shins and calves become heavier and your feet grow roots into the floor. Now breathe in slowly and breathe out slowly. Each time you breathe out, try to relax even more.

When you’ve got 10 minutes. Try imagery. Start by sitting comfortably in a quiet room. Breathe deeply and evenly for a few minutes. Now picture yourself in a special place. Choose an image that conjures up good memories. What do you smell — the heavy scent of roses on a hot day, crisp fall air, the aroma of baking bread? What do you hear? Drink in the colors and shapes that surround you. Focus on sensory pleasures: the swoosh of a gentle wind, the soft, cool grass tickling your feet, the tranquility of watching or listening to flowing water. Passively observe intrusive thoughts and then gently disengage from them to return to the world you’ve created.

Learn time-management skills. These skills can help you juggle work and family demands.

Confront stressful situations head-on. Don’t let stressful situations fester. Hold family problem-solving sessions and use negotiation skills at work.

Nurture yourself. Treat yourself to a massage. Truly savor an experience: eat slowly, focusing on each bite of that orange, or soak up the warm rays of the sun or the scent of blooming flowers during a walk outdoors. Take a nap. Enjoy the sounds of music you find calming.

Cultivate friendships. Having a core group of friends that you can do relaxing activities with and talk to can be extremely helpful in blowing off steam. Remember that friends are the family that you get to choose!

Talk to your doctor. Discuss with your doctor why you think that you might be stressed or anxious. Your doctor can give you strategic tips to help you or refer you to a specialist. If stress and anxiety persist, ask your doctor whether anti-anxiety medications could be helpful.

Are you a mean one, Mr. Grinch?

If your demeanor is more like the Grinch or Mr. Scrooge than Mary Poppins, you’re more likely to experience heart trouble. So says the literature on personality traits and heart disease, which has linked hostility, anger, and social isolation to a higher risk of cardiac woes.

The notion that personality can affect heart disease risk dates to the 1950s, when two cardiologists first observed that people with “Type A” personalities, who are hard-charging, competitive, and aggressive, are more at risk for heart disease than others. It turns out that’s not entirely true. Some Type A people are happy and healthy, while others are not. As research has continued into specific elements of the Type A personality that put people at risk, one trait in particular — anger — seems to be very toxic to the heart. People who are angry or hostile are two to three times as likely to have a heart attack or other cardiac event as others, according to one review article. Taming your rage with an anger-management program could help, however (see “Relaxation and your health”).

More recently, doctors have turned their attention to people with “Type D” personalities, who tend to have negative emotions, suppress these emotions, and avoid social contact. Although Type D’s appear to have poorer outcomes from heart disease, a 2011 study found no evidence of compromised heart function in people with Type D personality without documented heart disease.

Other research shows that men and women who live alone are more likely to have a heart attack or die suddenly from one. Adults who live alone are also more likely to smoke, be obese, and have high cholesterol levels than those who do not live alone, and they tend to see the doctor less often. On the flip side, older adults with a strong network of friends and family are significantly less likely to die over a 10-year period than those with a smaller network of friends. Friends and family, it seems, can inspire (or nag) you to take better care of your health. Divorce, loss of a spouse or companion, retirement, and relocation can all contribute to your becoming isolated from friends and family.

It’s possible that these personality traits and tendencies make people more vulnerable to stress, depression, and anxiety, which could explain the cardiac link. If that’s true, addressing those problems might help and certainly won’t hurt. And if your social isolation stems largely from circumstance, it’s worth making an effort to enrich your life by connecting with people. Take an adult education class, pursue a volunteer opportunity, join a book club, or take a walk around the neighborhood. Who knows, maybe you’ll experience a transformation like the Grinch, whose “heart didn’t feel quite so tight” at the end of the classic holiday story by Dr. Seuss.

Relaxation and your health

A modest but encouraging body of work shows some benefits to managing stress and anger. One study found that elderly people with hard-to-treat isolated systolic hypertension who underwent relaxation response training (see “Learn relaxation techniques”) were more likely to be able to effectively control their blood pressure to the point where they could eliminate their antihypertensive medications.

If anger is an issue for you, an anger-management program might help. An analysis of 50 studies that included almost 2,000 volunteers found that such programs help people tone down their anger, respond to threatening situations less aggressively, and use positive behaviors such as relaxation techniques or better communication skills. Other studies have demonstrated that improvements like these translate into lower blood pressure and better blood flow to the heart during exercise and stress. It’s not yet known, however, whether anger management can prevent coronary artery disease and reduce the likelihood of heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiac events.

An evaluation by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services examined two programs aimed at improving cardiovascular health through lifestyle modifications, including stress management, exercise, and nutrition counseling. The study, which ran from 1999 through 2007 and involved 589 patients who already had heart disease, evaluated two nationally recognized programs: one from the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine and one developed by Dr. Dean Ornish.

Both programs had a beneficial effect on cardiac risk factors; for example, participants lost weight, reduced their blood pressure levels, improved cholesterol levels, and reported greater psychological well-being. Participants in both programs also appeared to have better cardiac function. Moreover, participants in the Benson-Henry program had lower death rates and were less likely to be hospitalized for heart problems, compared with controls. The study concluded that these kinds of intensive lifestyle modification programs are clinically effective. While this study is good news for those with heart disease, more studies are needed to confirm these results.

Story Credit: http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/hearts-minds-how-stress-negative-emotions-affect-heart/