This Woman Thought She Had Anxiety, But It Was Actually a Rare Heart Defect

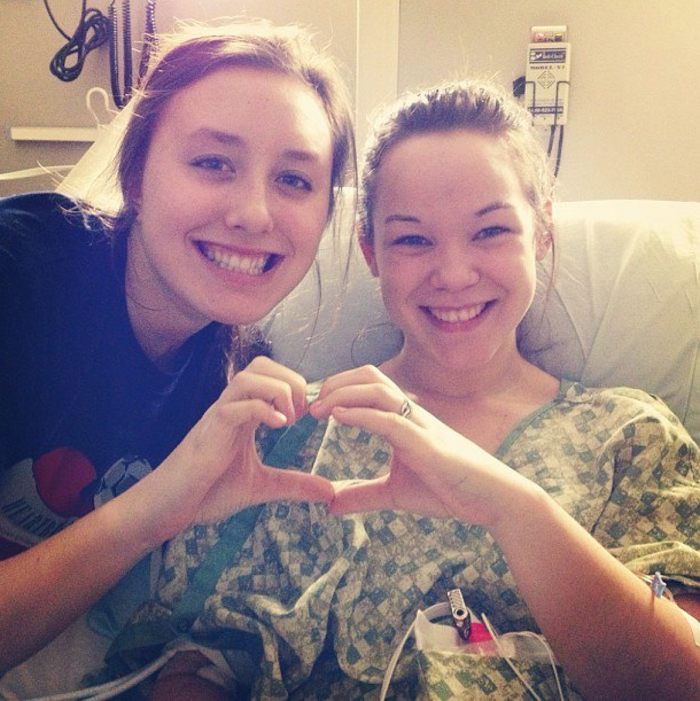

Photo: Heidi Stewart

Heidi Stewart swam competitively starting when she was 8 years old. Like a lot of athletes, she experienced post-race jitters, often feeling her heart beat out of her chest to the point of discomfort—but she always chalked it up to nerves.

By the time she turned 16, that feeling of discomfort resulted in a few fainting spells—and Heidi began wondering if it was more than anxiety. "I remember one incident in particular," Heidi tells Shape. "I was at this big meet and I got out of the pool after doing really well and my friend ran up to hug me. I immediately collapsed into her arms for long enough that paramedics were called; it was this huge ordeal."

After that, Heidi's mom decided to take her to a pediatric cardiologist to get her checked out. "We went there to run a series of tests, trying to cover all of our bases," Heidi says. "I was diagnosed with anxiety, and my doctor told me he didn't see anything wrong with my heart." Even though the doctor was concerned that Heidi was passing out all the time, he just told her to stay hydrated and eat better.

This diagnosis made Heidi feel like she was losing her mind. "I was an extreme athlete for my age," she says. "I ate incredibly well already and drank copious amounts of water while training and after—our coaches made us. So I knew that wasn't the issue. It was just frustrating knowing I had to go home once again, after costing my parents so much money, with no answers."

Then a few weeks later, Heidi was helping hang pink paper hearts around school for Valentine's Day when she started to feel herself pass out again. "I tried to grab on to a door handle in front of me and the last thing I remember is collapsing sideways," Heidi says. Her head barely missed hitting a copy machine.

The associate principal heard the fall and came to help, but he couldn't find a pulse. He started CPR immediately and called the school nurse, who arrived with an automated external defibrillator (AED), a portable lifesaving device, and called 911.

"I had flatlined at this point," Heidi says. "I had stopped breathing and blood was coming out of my mouth."

Clinically, Heidi was dead. But the principal and nurse continued performing CPR and shocked her with the AED three times. After eight whole minutes, Heidi got her pulse back and was rushed to the hospital where she was told she'd suffered sudden cardiac arrest.

In the ICU, cardiologists performed an echocardiogram, an electrocardiogram, and a cardio MRI that showed scar tissue on the right chamber of Heidi's heart. This scar tissue caused the right side of Heidi's heart to be bigger than the left, subsequently blocking signals from her brain to her lower right chamber. This is what had led to the fainting spells and irregular heartbeats that made Heidi think she was feeling anxious.

This condition is officially known as arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, or ARVD/C. This genetic heart defect affects about six in 10,000 people. And while relatively uncommon, it's often misdiagnosed. "Misdiagnosis is common, especially when the symptoms are vague, and can mimic other conditions that are more common such as anxiety," says Suzanne Steinbaum, M.D., director of women's heart health at Northwell Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. "That's why in cases like this it's so important to know your family history and to communicate it with your doctor, as well as pay attention, document the signs and symptoms being experienced and when they happen."

Following her diagnosis, Heidi underwent surgery where doctors implanted an internal defibrillator with a built-in pacemaker to shock her heart if she goes into cardiac arrest. There is no cure for ARVD/C, which meant Heidi needed to make a lot of life changes.

Today, she's not allowed to get too stressed or do anything that might cause her heart to beat too fast. She takes beta-blockers daily to help lower her blood pressure and can no longer swim competitively. Doing activities by herself is totally off-limits

Over the past five years, Heidi has worked hard to get used to her new life where the things she once loved have taken a backseat. But in many ways, she's incredibly lucky. "In some cases, you don't even know a patient had ARVD/C until after an autopsy," Dr. Steinbaum says. "That's why it's so important to advocate for yourself by getting answers to any questions, including the reason behind why symptoms are occurring. Being your own best advocate and getting diagnostic testing done when you feel like you should is a critical part of getting the care you might need."

That's why Heidi, who is now a Go Red Real Woman for the American Heart Association, shares her story to help inspire and educate women to help put an end to our number-one killer: cardiovascular disease. "I am so lucky to be here, but so many other women aren't," she says. "Right now cardiovascular disease kills approximately one woman every 80 seconds in the U.S. While that's scary, the good news is that 80 percent of those events could be prevented if people listened to their bodies, got educated, and made lifestyle changes. So listen to your body and fight to get the help you think you need."

Heidi also works to promote heart screening for young athletes. She hopes that these precautions will prevent other athletes from experiencing sudden cardiac arrest and potentially save young lives.

Story Credit: https://www.shape.com/lifestyle/mind-and-body/heart-condition-arvd-symptoms